In the kingdom of the blind, the one-eyed man is king.

- rjlucking66

- Jan 26, 2022

- 3 min read

Updated: Feb 12, 2022

Unseen terrors power an old pushbike through rain-lashed streets. An escape perfectly timed to coincide with an exodus of cyclists from the railway works. I am Eddy Merckx. I am Evel Knievel.

No one can catch me.

It is easy to get lost in a wet crowd, to disappear in the mass hurrying home.

My brother’s late Christmas present was a racing cycle that only saw daylight in dry weather.

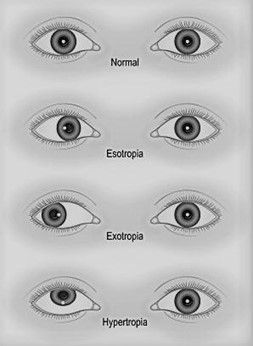

On discovering my plan to avoid a terrifying but necessary operation to correct a strabismus, a procedure that in those days involved a general anaesthetic and a lengthy hospital stay, our mother launched him and his treasured machine out into the deluge in pursuit.

He caught me amongst the ignoble wheeltappers and shunters, streaming, steaming, storming hungry, homeward throng who refused to accept his explanations that he was engaged in a medical emergency of sorts. A gallant effort for which he was disgracefully racially abused.

I rewarded him by clawing at his afro and crying my way to the operating theatre, where a surgeon attached a speculum to my eyelid and detached a muscle connected to my wonky esotropic eye. Moving it into a new position and holding it taught with dissolvable stitches, ensuring that my eyes pointed in the same direction for the first time since I emerged from the womb.

Swaddling bandages bring blindness, a feeling of complete all-encompassing helplessness.

My mother drowning in obedience visits and cries. My pragmatic and less deferential stepfather corners a reassuring consultant who says, “he’ll be fine.”

My place of incarceration is the ward where I had visited the boy who lost an eye in the Summer of war and a school friend who crippled himself by jumping from a third-story classroom window for a fag.

Alb reads from a selection of Kinder und Hausmärchen by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm refusing to leave my bedside, his reassuring presence preventing a slide into loneliness and hypochondria.

The bandages are removed, my sight gradually returns, albeit veiled by tiny blood spots and I watch through a cracked and rattling window as radiant shafts of light flicker and pierce the clouds, until he has gone.

The delayed medical intervention came too late, a child’s visual pathways are fully formed by the age of eight. My eyes had stopped working together, each sending a different image to the brain. This would normally result in double vision in an adult, but a developing visual system adapts, ignoring the image coming from the eye with the squint. The brain suppresses the vision from the squinting eye and in my case, this ‘switching off,’ caused the vision in my right eye to weaken as it was not being used.

It is important to treat childhood vision problems before the visual pathway is fully formed, failure to do so left me with an amblyopic right eye. There is no treatment to correct amblyopia in adults.

The poor vision in my right eye reduces depth perception making it difficult to judge distances and is a pain in the arse when trying to watch a movie in 3D.

During an active discussion, my wife speculates that this may explain why I am unable to see love.

The vivid memory of those hospital days provokes questions.

Why do such incidents throw up tornadoes of tumultuous emotional force and existential alienation?

Was it negligence or abandonment that created this short-sighted neurotic perpetual migrant who belongs nowhere?

A man-boy with an inner void, a chasm of unfulfillable needs and failed relationships. An innate distrust of medics, of authority, and the powerful who cajoled and acquiesced.

A belief that no one could ever act in his best interests is driven by primaeval fear, a Tyrannosaurus Rex intent on devouring waits.

Psychotherapy urges us to face reality, but what if that reality or our version of it is too painful, is the very thing that will obliterate us?

Questions that give us no peace.

Comments